Lava flow from Kīlauea Volcano, Hawaii Photo: Mathilda Tómasdóttir

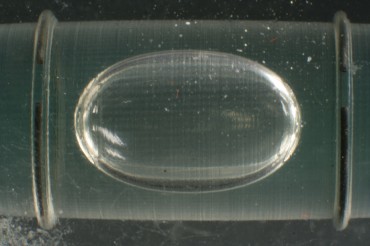

Level to check the horizontality / verticality Photo: David Torno

16.7.2014 – Issue 13 - Water – Hampe Michael, Sauter Florian – Studio

Panta Rhei and Plato's Revenge

Lecture by Michael Hampe

Philosophy is usually concerned with concepts; abstract concepts like

causality or space and time. Water is not so much a concept as a kind of

pre- or proto-concept: a word that was used before conceptual thinking

really began.

Pieces of water

If you cut this building into two parts, you do not get two buildings; you

get a broken building. Conversely, if you cut water, you get water. You can

divide water—if you do not go too far, like chemists do—into pieces of

water. This is called homogeneous division: elements can be divided homogeneously,

whereas individuals can only be divided heterogeneously.

The modern term for things that can be divided homogenously is mass.

Words like water, air, mud and earth are mass terms. These mass terms

were used in philosophy before concepts.

Earth: a type of water

The quite straightforward idea defended by Thales was that our earth is

frozen stuff that originates from something fluid. Water was a principle for

explaining why something is fluid; you explain why something has a given

property by referring to parts of that something. Thales probably saw

fluid coming out of a volcano, then solidifying to become like earth, and

therefore referred to the fluid emerging from a volcano as a kind of water.

He envisaged a kind of water beneath the earth’s surface. In philosophy,

many authors use the metaphor of ground or even the foundations of a

building as justification. It sounds paradoxical, then, to believe that something

firm rests on something that is not firm, something that is floating.

States of water

The idea of explaining something as an element is usually connected

with the word arche, which is sometimes translated as “principle” but

usually refers to “origin”. The idea of water being an arche before any

theory of evolution suggests that everything comes from water: if you

stretch water, you get steam and gas; if you compress water, you get

earth and firm things. We come to this conclusion because water is the

only element that exists in all aggregate states without any technical

manipulation. The realisation that clouds, steam and ice are all types of

water might prompt the belief that there is an original state of the element,

a fluid state that can be stretched into a gaseous thing or element,

or compressed into a firm, earth-like thing. So wetness and fluidity were

considered the most fundamental properties of all elements. The other

elements could then be deduced from water, making the idea that living

creatures with fluid and firm parts come from water very plausible. With

knowledge of how water can change, the idea of water as the origin of the

other elements and of living beings is plausible.

Swirl in the river

I started by saying that water is not an individual that can be divided by

heterogeneous division like a normal individual. Nevertheless, it becomes

an individual when it is contained in earth-like shapes such as rivers,

lakes or oceans. Once contained in a certain shape, water is no longer

homogenously dividable; you cannot cut a river or a sea into homogeneous

parts. Individualised water presents the paradox of something you

can come to again and again, but which is constantly changing. In this

case, water is not a substance, because substances are proper individuals

in which change takes place. The process philosophers turned this

around: a constant pattern of change is responsible for there being substances.

One example is a swirl in the river: the river is constantly moving

and the water is constantly changing, but a swirl looks like a more or less

defined figure in the river. Similarly, you could say that you are the person

you are because of the actions you do, rather than you do those actions

because of the kind of person you are.

The issue

This idea of constant change using the analogy of water was very common,

but it was not to Plato’s liking. Heraclitus saying, “We step into the

same rivers and we do not, we are and we are not” (DK 22 B 49 a) was

repulsive to him; it was a contradiction. Knowledge has to do with the

relation between properties and individuals. Now, if properties come and

go because everything changes, then you can never have knowledge

about anything. For Plato, this was a disaster; not having knowledge

about anything means having no orientation; it is like being at sea with

no horizon in sight, where nothing is fixed. It is no coincidence that the

process philosophers liked water and the sea so much, because the sea

is a place where it is extremely difficult to orientate yourself.

Plato’s concern

“I will tell you and it is not a bad description, either, that nothing is one

and invariable, and you could not rightly ascribe any quality whatsoever

to anything, but if you call it large it will also appear to be small, and light

if you call it heavy, and everything else in the same way, since nothing

whatever is one, either a particular thing or of a particular quality; but it is

out of movement and motion and mixture with one another that all those

things become which we wrongly say ‘are’—wrongly, because nothing

ever is, but is always becoming. And on this subject all the philosophers,

except Parmenides, may be marshalled in one line—Protagoras and

Heracleitus and Empedocles—and the chief poets in the two kinds of

poetry, Epicharmus, in comedy, and in tragedy, Homer, who, in the line

‘Oceanus the origin of the gods, and Tethys their mother’, has said that all

things are the offspring of flow and motion; or don’t you think he means

that?” Theaetetus, 152 d

Oceanos and Tethys, those very ancient gods or giants, are supposedly

the origin of all things, and Plato saw himself as fighting an army of thinkers

and poets who were all wrong, because they believed that everything

changes and did not realise that this viewpoint represents the loss of all

knowledge.

The solution

Plato’s alternative was the production of concepts. He presupposed that, in

order to have knowledge of something, we need to recognise it; we have to

be aware that this chair is the same chair we have seen before. In order to

be able to do this, we need a concept, the Greek ideos, according to which

we see this wood and metal before us as a “chair”. We could say that this

chair is a state of tree; the tree was first a germ, then it had leaves and it

ended up as something you can sit on. But we say it is a chair, not a state of

a tree. What, then, enables us to say that this piece of wood is not a state of

a tree, but a chair? It is the way, the idea, under which you consider it. And

where do these concepts come from? For Plato, they are not visible, they

are abstract. According to him, they come from mathematics; if I say this

wood is circular, the idea does not come from the wood itself, but I apply

it to the wood. So I make this chair into something constant by applying

abstract ideas to it. The way in which Plato avoided the flow of matter, the

wateriness of everything we experience, was to invent lots of abstract

structures that cannot change—at least not in the world of experience.

The interest in certainty

If you are not interested in knowledge, you do not need these abstract

structures. If you are only interested in experience, there is no problem with

things constantly changing. We might still be talking about the whole world

as element-like structures if we had not been interested in a certain kind of

knowledge: knowledge that does not change. The idea that there is something

that does not change has to do with an interest in certainty.

Question I: the horizon - the idea of a line

I don’t know when the water balance was invented, but it would be a good

anti-Platonic argument to say that the most fundamental geometric idea—

the straight line—comes from water, something commonly associated with

change. That’s a good point.

Question II: Ice

Ice plays a very small role in philosophical thinking about water, probably

because it is so hot in Greece that you hardly ever find ice. The Eskimos

would have probably first thought of water as ice melting.

Notes by Florian Sauter

Download article as PDF