Selected Topic

Issue 8 - Middle East 2 – Prospects for Architectural Practice (April 2012)

Show articles

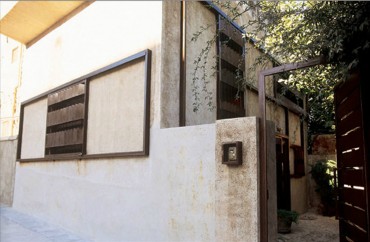

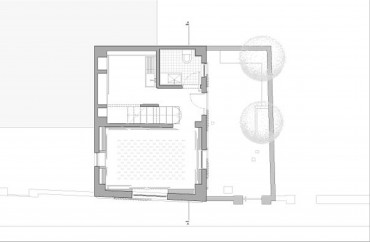

Clinical Psychologists workspace, 2001, Jabal Amman

Clinical Psychologists workspace, 2001, Jabal Amman

Clinical Psychologists workspace, 2001, Jabal Amman

Clinical Psychologists workspace, 2001, Jabal Amman

Clinical Psychologists workspace, 2001, Jabal Amman

S-House, 2005, Abdoun, Amman

S-House, 2005, Abdoun, Amman

S-House, 2005, Abdoun, Amman

4.7.2012 – Issue 8 - Middle East 2 – Ivanišin Krunoslav, Al Asad Mohammad, Al Hiyari Sahel – Interviews, Videos

THE BEST ART SOMETIMES COMES FROM RESTRICTIONS

Interview with Mohammad Al Asad and Sahel Al Hiyari

Public space in a Middle Eastern city

MOHAMMAD AL ASAD: this is a very difficult subject to address because there is always the talk of the fact that there are no true public spaces in this part of the world, but then you have Cairo and “Tahrir square” which shows how a public space does exist. It was really fascinating how people took control and ownership of it, I mean you had a group of people who would collect the garbage and recycle it, you had a pharmacy, you had a child care centre all created in that public space, it was a truly public space and people took ownership of it, but unfortunately we do not have in the modern sense of the world public space that we really use where people use and feel sense of ownership, at this stage looking at public spaces in Amman we feel these places have become places of social tensions rather than places where people come together.

SAHEL AL HIYARI: I don’t know, because, while you were talking, what comes to mind is Egypt and actually this idea that one nation should look at it anthropologically and culturally, and how in Egypt the relationship to space is entirely different to what it is in Europe, even here, what you call a public space is not necessarily something categorized and well defined, it is something very malleable. A sidewalk can become a mosque, a side walk can become a playground, under a bridge you can build a building, therefore it’s very difficult to sort of compare it to the notion of public space in Europe and also I think in Europe it’s not a monolithic thing, it’s very different from one city to another. But I do think what is even more dangerous is to try to bring that model here because often when that happens it results in the cleansing of the city, the city becoming deodorised and the city becoming sterilised. Because what remains out of this idea of public space is just form and not use, all of a sudden you have a space that becomes, for example like the Solidaire in Beirut, almost like checking into an airport, you have guards guarding it, and you can use it only in a specific way and so the sense of public and ownership of the space no longer exist.

So in that sense when you try to bring one model and sort of graft it into another culture entirely you get a very odd result and also unexpected.

Contemporary architectural reality of Amman

SAHEL AL HIYARI: Schizophrenic (laughs)… I think to a large extent it is the generic architecture that is being produced and that is proliferating and that is making up 99.9 percent of what is happening, as it is in the rest of the world. When we look at publications and all these wonderful buildings in those glossy high end magazines... they do not really describe the condition of architecture in the world. They are actually taking a very small segment and representing it, but the majority of what is being built in the world is unfortunately very generic and is in many ways substandard in so many places... I think, yes, there are experiments in the Middle East in general, the region in general, that are very interesting and they do draw on the context where they find themselves situated.

What do you think? (to Mohammad)

MOHAMMAD AL ASAD: I agree with you, but I would look at it maybe from a different angle. You are seeing tremendous growth, and growth is double edged. On one hand you have the substandard that you mentioned. And I think one of the problems of the modern era, in contrast with the traditional periods where there was a certain standard that applied to all, is that we have lost that standard. If you look at the building stock that comes out of the 30’s and 40’s in Amman, there is a certain standard that is quite high. Now everything goes! But the good side of things or the more positive side is that there is a really great deal of energy going on and with that energy you get here and there some very high quality works, and very creative works, and that is interesting. I enjoy looking at that.

SAHEL AL HIYARI: Possibly also a part of the formula is the fact that you can actually build. I mean I have friends who practice in London and they say you can’t do anything there because everything is so regulated. It is another double edged saw, and that actually can become very interesting because you are witnessing a process of formation of some sort and you can actually contribute to that formation. It is not something that is well established and finished and it is not a complete project. Actually, architecture in Jordan is an incomplete project, it is ongoing, and it can actually constitute very interesting challenges and at times aid in coming up with alternative design strategies that are suited only for that particular context. I think, from my experience working here, it is this ongoing negotiation with the context whether its geography, history, the culture of construction is also very important, the cultural dimension of the client is a world in its own... so when you bring all of these things together to the table, and you design, all of a sudden what happens in Tokyo doesn’t become as important because you have a completely different set of things that you need to deal with. You cannot concern yourself with standards that are used in other places, when you look at the reality you really deal with the reality itself, and actually to really extract from that reality a possible move of operations.

MOHAMMAD AL ASAD: One way of reading what you are saying is that often when you look at more mature centres of architectural productions like America or Europe, it is very stifling, you can almost tell what is going to appear. There is a very rigid way of doing things, there is a very strong architectural culture, and you have to fit within that. Here everything goes, there is craziness but also inclusive, open to ideas, so you might get very bad work, but you also get the chance to experiment. A colleague of ours mentioned something interesting; that we live on the edges of the architectural world. This is not where projects in the international magazines are. It gives you a sense of freedom, you can try new things which you could not probably be able to do in other cities like London, New York...

Specifically Jordanian in the contemporary Jordanian architecture

MOHAMMAD AL ASAD: Definitely, the most direct and what comes to mind first is stone! But also you have architects like Sahel that define their work as an antithesis to stone. As an example, in the office he designed for the psychologist, he said I’m staying away from stone, even though it is the primary material in that neighbourhood.

But also in Amman the topography is very powerful you cannot ignore it, and the climate...

SAHEL AL HIYARI: It is clearly formed by very specific forces that created it. If you drive around Amman you see a building looking like Mendelssohn or another building that looks like Zaha or wants to be looking like Zaha... you have this mish-mash of styles, and at the end of the day it is this mish-mash what actually is the character of the place, the character of contemporary Amman. In a sense they all have to react to particular things; construction budgets, materials, techniques, know-how, the skills, and at the end of the day we depend on the workers that come from Egypt and they work in this country and they built what we know as contemporary Amman. So all of these aspects have the imprints, and this is what forms the genetic structure of the architecture here and now. Certain deviations, like it is not going to be stone, or designed in that manner or so on, are addressing certain aspects and it’s how you actually subvert them and how you expand their limits, because we talked about freedom but at the same time we have a lot of limitations and these limitations are what sometimes give us that freedom.

Advantages for architectural practice in Jordan

MOHAMMAD AL ASAD: Growth, it is a growing country, so there is room to do things. It is a place that is growing, it has a large young population that is always bringing new ideas with it and they are expecting new things, so there is that excitement of experimentation in Jordan that you do not feel in more mature settings.

SAHEL AL HIYARI: I would say also the margin...

MOHAMMAD AL ASAD: Yes, you´re not under the microscope, you are not being monitored.

Is that a good thing or a bad thing?

MOHAMMAD AL ASAD: I think it has wonderful opportunities; well it gives people the options to be shoddier than usual and at the same time it gives them freedom. I mean some of the current architecture approaches are starfling in their limitations, if you look through what was taking place in the last 10 years, and it seems very repetitive.

Do you think this lack of critique, or microscope is a cause for what Sahel mentioned about architecture in this area as schizophrenic?

MOHAMMAD AL ASAD: I think the schizophrenia comes from another set of reasons. We are torn between two worlds. We are connected to the West, we were educated there, we use their products, all sorts of technologies. At the same time we have our long deep history that we are proud of and we are always torn between them. I find the lack of monitoring to be sometimes refreshing. It gives you a sense of freedom. Ideally, we should have a more developed tradition of criticism. I hope as this set of criticism evolves, it will be more open to inclusion, while I see the criticism coming out of the West very limited in its scope, it idealizes what is fashionable in that stage and looks at all the others as out of touch, and I think we have the opportunity to create something quite inclusive.

Sahel’s projects that describe Jordanian context

SAHEL AL HIYARI: That’s difficult because there´s a little bit of schizophrenia there... (they laugh)

Mohammad Al Asad: My favourite is I think your second work. It’s the psychologist’s clinic; it is the one I always refer to. I will begin with an anecdote (…) he did it on a budget of 15,000 USD which is self remarkable and he just used the most basic materials and construction techniques, and that’s what Sahel mentioned about how you have to interact with the local realities. I mean in Jordan you have this shoddy concrete work where rust begins to start, so he consciously added rust to the concrete, the lighting he had these galvanized water pipes, he made the sinks at some stone maker. He took what you find around in Jordan and created a spectacular work of architecture from it. I think sometimes someone has to force you to do something with a 10,000 dollar budget and then you will see brilliant things coming out. You know, as James Joyce said, that the best art comes out of restrictions! And that restriction Sahel dealt with brilliantly.

Interview by Ala’ Zreigat and Krunoslav Ivanišin

Download article as PDF