Selected Topic

Issue 8 - Middle East 2 – Prospects for Architectural Practice (April 2012)

Show articles

Mellat Park Cineplex, Tehran, 2008

Mellat Park Cineplex, Tehran, 2008

Mellat Park Cineplex, Tehran, 2008

Ave Gallery, Tehran, 2000

Ave Gallery, Tehran, 2000

Ave Gallery, Tehran, 2000

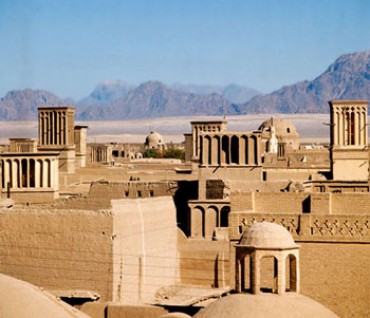

Yazd, traditional city

Safaeie Residential Complex, Yazd, 2006

Safaie Residential Complex, Yazd, 2006

Safaeie Residential Complex, Yazd, 2006

4.7.2012 – Issue 8 - Middle East 2 – Ivanišin Krunoslav, Ghasemizadeh Saba, Daneshmir Reza, Spiridonoff Catherine – Interviews

THE WILL FOR CHANGE

Interview with Reza Daneshmir and Catherine Spiridonoff

There is a certain romantic aspect to the Middle East, very hard to avoid when we look at it from a European (“Western”) perspective: mythical place from books where anything can happen. How does the contemporary Middle East look like when seen from inside, related to architectural project and in architectural discourse? What is “Middle East” from the perspective of a practicing Iranian architect?

We believe that the contemporary architectural projects and discourses are in transition from the old patterns and concepts to the new fresh spaces and structures. This is how every living society should be, and it doesn’t mean that this freshness kills the old one; however, many architects here still insist on traditional values and see Iranian identity in repeating exactly those patterns and clichés. This discourse goes on and on and never ends.

The Middle East is a new landscape of unexpected potentials, because it’s yet under development with elastic rules or you can even say, fluid rules - for the reason that the previous (or some might say modern) rules have been broken by revolutions, wars, etc. You can feel that this is a new society with a new generation of young people who want to change everything. Gradually we see that the new generation of young Iranian architects is emerging on the scene with their small projects, mostly private houses and a few public projects that can affect the city and the society, and make them think about different kinds of architecture. Maybe in few years from now we might be able to talk about the new Iranian architecture.

Is it possible to apply the European notion of “public space in the city” to the contemporary Iranian situation? How would you describe in short the structure of urban spaces in a typical Iranian city, considering the relation between the exterior (“public”) and the interior (“private”) spaces?

The question is “How?”.

What you learn from the books is that in the typical Iranian cities, the structure of urban spaces was a bazaar that accompanied with a maidan (public square), The mosque and a palace. The bazaar was the spine and city was formed around it. But we think, maybe it’s not the whole story. Since most traditional cities in Iran were located in dry lands, people came to the invention of qanats around 6000 years ago and devised very specific systems of canals deep underground that could bring fresh water from the hills to the cities and distribute it through the vein system of a sort to everywhere. We think this is the main structure of the ancient Iranian cities.

Our answer to the question “Is it possible to apply the European notion of public space in the city to the contemporary Iranian situation?” is yes. But first we have to x-ray our cities and map the very significant structure that hides beneath them, then work on them and reactivate them in new ways for new kinds of public spaces

How would you describe the contemporary architectural reality of Tehran?

Today, in architectural practices we see different projects. Some want to do traditional architecture or make something which looks like it, some want to be minimalist just doing their program, and some want to experience new structures and spaces... it depends on clients and architects. Many clients or architects don’t want to venture; so opportunities come and go, and nothing happens. But in some cases, some architects can by nature convince their clients to do different things. Those projects can affect their environment, and when strategically located, they can affect the city. That’s what happens in Tehran.

Iran has always been an interesting place from many different perspectives. Is there something specifically Iranian in contemporary Iranian architecture, related to the specific context, to the specific material conditions, to the traditional concepts of space?

Yes, of course. In different projects it happens. A city like Tehran is more or less an international city – in some locations there, like The Old Tehran or the north part of the city which has gardens and mountains, you can find specific locations that need attention, but in other situations, it is not totally different from other cities.

Brick is still one of the most favourite architectural materials here and you can find many good new brick buildings, but our concern is the internal empty space, court, or you can say void. We think this is the most significant concept of the Iranian architecture for thousand years, because it’s like the main anchor and every other spaces and programs are arranged around it. It’s an organizer but at the same time brings light, life, green space and most importantly a kind of public space in a private situation. In traditional architecture it happened in plans, but we like to use it in sections.

What is to your experience the most important developmental advantage of the contemporary Iran? How does this advantage affect architectural practice?

We think the most important developmental advantage of the contemporary Iran is “the will for change”, but it’s very difficult and has not happened yet.

Would you describe yourself as a “Middle Eastern, Iranian architects” or just “contemporary architects working in Iran”? What were your major architectural references during the studies and what are your architectural references today?

We think both. We know what’s going on in the world and we also know the political, economical and cultural situations in Iran; therefore, we can put together our knowledge from these sources and invent new kinds of organizations and spaces. Before and during the architectural studies at university, we studied music and painting; so our thoughts and points of view were deeply rooted in these two disciplines.

Architecture gets started with an observation and the observation brings up the potentials and clues to reach the concept. We think architecture is the “invention of structure” which is based on observing the subject and the related phenomena. Thus, in every project, our effort is to set ourselves free from our previous knowledge and reach the “empty” emotional and intellectual level, which is in need of focus and peace. Then from that level we start observing that special project or matter. Also, sometimes while working on a project with a different subject, we find something else by accident; therefore, accidence in observation plays an important role and a wide range of knowledge will be gained from accidental observations.

How would you evaluate the architectural education in your country? What is your experience in the public discourse on architecture?

Times ago major architectural schools in Tehran were based on beaux arts, but since the revolution, we think we haven’t had a school of architecture like Western schools that stands for a specific direction. In Iran, architectural schools teach general knowledge of architecture and that’s all about it.

Could you choose and describe shortly one of your projects that defines your designer attitude in relation to the Iranian context?

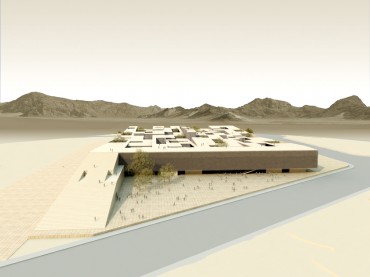

The Safaeie Residential Complex project in Yazd was awarded the second price in the architectural competition with 52 architectural firms involved.

Yazd is a horizontal city with green holes and narrow alleys with long shadows and smooth three dimensional surfaces of roofs; sticking to the ground, unified, monochrome, cool, soft and deep; a miniature space where unique event is happening in every corner. Although the project was situated in the southern part of the city, far from its old and precious texture, the purpose was to create a connection to it and point out those features of the traditional architecture which have the ability to develop in space for today’s demands.

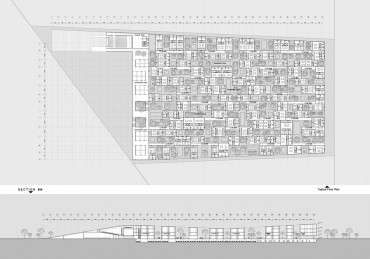

By dividing the trapezoid site into a rectangle and a triangle, the basic geometry of the project was defined. The triangle part, which is next to the main boulevard, was considered as the entrance plaza to the complex; the rectangular part was defined as the main built volume. All the public areas, such as the commercial, official and cultural spaces, were organized in an L-shaped volume in three levels in between the triangle plaza and the residential rectangular part; defining thus the northern and the eastern sides of the plaza.

The L-shaped roof gets connected to the plaza from the north side by a mild slope, making it possible to have a continuous movement from the entrance plaza to the roof. The residential volume is a porous mass in two or three levels which is connected integrally to the L-shaped service volume, giving a cohesive texture to the whole complex. The parking lots are situated in the northern and southern frontiers, access to which is possible from all the units through the vertical access cores. The middle part, like a continuous garden in the ground floor, creates the main internal green spaces of the complex. It gets the natural light through the big voids in between the units.

The project has three main parts:

1) The triangle-shaped entrance plaza

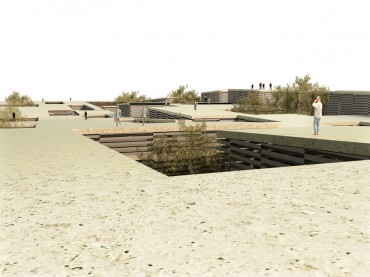

2) The semi-private rectangular-shaped gardens (voids)

3) The extensive and wavy roof terrace which creates the fifth façade.

The continuity between these parts makes the natural ventilation, natural cooling and air circulation easier. It also provides various and unexpected perspectives to the residents.

The triangle plaza is the main entrance to the complex and it provides a gathering space for the residents. Not only it provides a space for special ceremonies but also it gives a special character to the complex due to its solid geometry.

The internal gardens have unique features. They provide moisture and sufficient light due to the fountains and trees suitable to hot-and-dry climate. The wavy roof with its vast and mild slopes is a completion to the public spaces. This roof which is connected to the main plaza through the mild slope can be considered as an urban terrace which welcomes the residents in suitable seasons.

Interview by Krunoslav Ivanisin and Saba Ghasemizadeh

Safaeie Complex, Yazd

Client: Yazd municipality

Architects: Catherine Spiridonoff, Reza Daneshmir

Design Associate: Iman Nedaei, Amir Badiei, Mohamad Mehrabani, Iman Daneshvarnejad, Akram Lolaei. Total Area: 36,000 m2

Download article as PDF