Selected Topic

Issue 8 - Middle East 2 – Prospects for Architectural Practice (April 2012)

Show articles

Doha, Desert and City (Source: K.Ivanisin)

Doha Now: The Reaction and Result of the Global Condition (Source: A. Salama, F. Wiedmann, A. Thierstein)

Doha Then: The Pre-Oil Settlement in 1947 (Source: A. Salama, F. Wiedmann, A. Thierstein)

Souq Waqif during the day; a catalyst for urban diversity (Source: A. Salama)

Souq Waqif at night, a sustained vibrant urban space (Source: T. Makower)

Msheireb Urban Regeneration Master Plan by a consortium of AECOM, Allies and Morrison Architects, and ARUP (Source: T. Makower)

Al-Barahat Square by Mossessian & Partners (Source: ©mossessian & partners)

I.M. Pei’s Museum of Islamic Art (Source: A. Salama)

Doha’s West Bay Business District (Source: A. Salama)

Multiple Performers Compete in Creating a Unique Urban Image (Source: A. Salama)

Isozaki’s Liberal Arts and Sciences Building at the Education City (Source: A. Hasanin)

Legoretta’s Texas A & M Engineering College at the Education City (Source: A. Hasanin)

The Pearl Development: A New Lifestyle for an Exclusive Segment of Society (Source: F. Wiedmann)

The Pearl Development: Eclectic Mediterranean and European Style utilized for image Making (Source: A. Salama)

4.7.2012 – Issue 8 - Middle East 2 – Salama Ashraf – Essays

NARRATING DOHA'S CONTEMPORARY ARCHITECTURE: The then, the now - the drama, the theater, and the performance

by Ashraf Salama

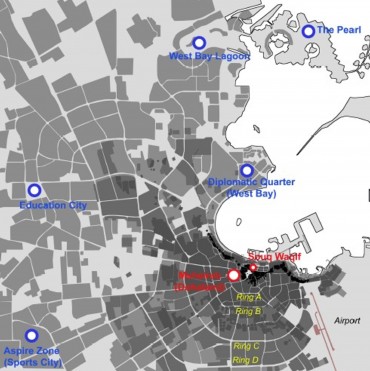

Doha, the capital of Qatar, keeps positioning and re-inventing itself on the map of international architecture and urbanism with different expressions of its unique qualities in terms of economy, environment, culture, and global outlook. In many respects, it is pictured as an important emerging global capital in the Gulf region with intensive urban development processes. In this essay, I introduce a narrative of Doha’s contemporary architecture that resembles a drama for a theater with performers contributing to scenes exhibited to the local public and the global spectator .

Doha Then and Doha Now

Historically, Doha was a fishing and pearl diving town. Today, the capital is home to more than 90% of the country’s 1.7 million people, with over 80% professional expatriates from other countries. Up to the mid 1960s, the majority of the buildings were individual traditional houses that presented local responses to the surrounding physical and socio-cultural conditions. During the 1970s Doha was transformed into a modernized city. However, in the 1980s and early 1990s the development process was slow compared to the preceding period due to either the overall political atmosphere and the first Gulf war or the heavy reliance of the country on the resources and economy of neighboring countries.

Over the past few years, the city has acquired a geo-strategic importance. Through the shift of global economic forces, it is being developed as a central service hub (together with other major cities in the region such as Abu-Dhabi, Dubai, and Manama) between old economies of Western Europe and the rising economies of Asia. In the context of international competition between cities new challenges are emerging. Cities need to find ways to sustain and extend their position. No doubt, architecture and the overall urban environment are tools utilized by governments and decision makers to help cities survive in the global competition of geographic locations. Like its neighboring growing capitals, Doha has ambitions and aspirations and in attempting to distinguish itself on the world map, its architecture is dynamic and is continuously materializing its aspirations.

The Drama: Cultural Politics

Using the allegory of Drama to reflect on Doha’s architecture requires giving a glimpse of what Drama is about. The term means any situation or series of events having stunning, poignant, conflicting, or prominent interest or outcomes. Drama is the specific mode of narrative (fiction or non-fiction), which is represented in a performance. It involves not just the narrative; it is performed by actors before an audience and engrosses collaborative modes of production and a collective form of reception. This is the case of Doha’s architecture. Drama is the narrative behind the public face of its buildings. The actors are mostly international architects who are working with and for client organizations representing different interests and cultural positions. The audience is mixed and is represented by the local community, the average citizen, the expatriate professional, the tourist visitor, while also speaking to the global world. Here, the narrative of Doha’s architecture encompasses an important element; cultural politics.

Qatar is an Arab and Muslim country, it is part of GCC-Gulf Cooperative Council and has strong cultural and religious ties with Mediterranean countries. What does this tell us? It says that there is an amalgam of influences that can be seen within models of cultural politics. There is somehow an influence of "Pan-Arabism" a secular Arab nationalist ideology framed to constitute one nation of different societies, from the Atlantic ocean to the Arabian sea, bound together by common linguistic, cultural, religious, and a shared historical heritage. There is also an indirect influence of ‘Islamism,’ that offers an ideology which largely displaced ‘Pan-Arabism.’ Across the Gulf, the influence of ‘Islamism’ may also be seen as coming from Contemporary Persia as it used to flow in the past.

What is more, there are ‘Mediterraneanism’ and ‘Middle Easternism’ that have been described as ‘partnership’ and ‘conflicting’ models. Both include polar partners and in the context of globalization none of the partners can ignore others where the main characteristic is the downfall of barriers between regions and societies. These four models are challenged by ‘nationalist particularism,’ which is becoming the norm in most Arab countries. While these models are constructs that serve political ends, they are of important heuristic value. They bring into focus questions about identity and the sharing of deeper meanings at the cultural and human existence levels. The unique cultural and geopolitical position of Qatar, coupled with the contemporary global condition, created a rich soil (the theater) for architectural experimentation (the performance) where a considerable number of physical interventions (the scenes) have emerged toward originating identity and in search for meaning.

The Theater in Doha: 6 Architectural Scenes

Theater is generally defined as a form of art that is collaborative in nature with live performers presenting the experience of an imagined or a real incident or event before an audience. Typically, the performers communicate such an experience to the audience through various means including speeches, songs, music, dancing, gestures. Yet, in narrating Doha’s architecture and urbanism, I argue that performers communicate a real event to the public through architecture.

Scene 1: Souq Waqif

The remanufacturing or reconstruction of Souq Waqif is an important scene that represents the aspiration of conserving the past of a nation. The literal translation of the area is “The Standing Market,” a Souq with an history said to span across 200 years. It contained different types of sub-markets for wholesale and retail trades, with buildings characterized by high walls, small windows and wooden portals, and also open air stalls for local vendors. Bedouins used to hold their own markets on Thursdays selling timber and dairy products. Also, it was a gathering space for fishermen. Over a period of three decades from the late sixties until early 2000s, the Souq was derelict and most of its unique buildings fell into gloominess. With an initiative from the PEO-Private Engineering Office of the Emiri Diwan, the Souq has acquired a new image by returning it to its original condition. However, while it kept its function, new arts galleries, traditional cafes and restaurants, cultural events, and local concerts were introduced as new functions attracting most of the city residents and visitors. Despite some criticism in seeing its architecture as eclectic, I argue that Souq Waqif can be portrayed as an exemplar of urban space diversity in the Gulf.

Scene 2: Msheireb Project

This is a scene for urban regeneration and a reinterpretation of traditional architecture, with a Master Plan developed by EDAW-AECOM design and planning. The scene is developed to bring Qatari families back into the heart of the city while restoring a sense of community. Notably, attempting to balance global contemporary aspirations and the re-interpretations derived from traditional environments, projects within the Master plan endeavor to recount spatial and visual language concerns in an integrated manner. Diwan Amiri Quarter of the larger Msheireb urban regeneration project, which is designed by Tim Makower, Principal of Allies and Morrison, attempts to create an intervention that is not just a glass or metal greenhouse but rooted in Qatari culture. Al Barahat Square of Mossessian and Partners is another scene within the larger scene, which would act as an urban lung for the development while drawing on the Qatari traditional architecture as a main quality of the surrounding buildings.

Scene 3: MIA-Museum of Islamic Art

Typically in museum scenes, the relationship between the building from inside-the elegant receptacle and its outside-the spectacle appears to be paradoxical. Such a relationship seems to be well addressed in the I.M. Pei’s Museum of Islamic Art in Doha. Dedicated to reflecting the full vitality, complexity and multiplicity of the arts of the Islamic world, the Museum of Islamic Art collects, preserves, studies, and exhibits masterpieces spanning three continents (Africa-Asia, Europe) from the 7th to the 19th century. The Museum is the result of a journey of discovery conducted by Pei whose quest to understand the diversity of Islamic architecture led him on a world tour. Influenced by the architecture of Ahmad Ibn Tulun Mosque in Cairo, the museum is composed of two cream-colored limestone buildings, a five-story main building and a two-story Education Wing, connected across a central courtyard. The main building’s angular volumes step back as they rise around a 5-story high domed atrium, concealed from outside view by the walls of a central tower. An oculus, at the top of the atrium, captures and reflects patterned light within the faceted dome. In addressing the notion of receptacle and spectacle, the building has a strong presence from the outside and dramatic scenes from inside. Here, I argue that the scene is a conscious performance for translating the cultural aspirations of a country into a manifestation that speaks to world architecture while addressing demands placed on the design by the context and the regional culture.

Scene 4: The West Bay Business District

The emerging business district named ‘West Bay’ is a scene, with multiple competitors. It presents a newly developed central hub. Through promoting new work and lifestyles, a new urban image and a stunning skyline are generated . The West Bay is a high density development consisting of high cost-high rise glass towers. While it has generated a stunning image that became a characteristic of the city, individual buildings are competing to position themselves within the skyline while offering a dramatic departure from typical designs of urban high-rise towers. One would note three major competitors in the scene. The first is Al Bidaa Tower by the Australian consulting firm GHD, with a continually twisting form and a rotating floor plan with multifaceted curtain wall that reflects sunlight during the day and artificial interior light at night. The second competitor in the scene is Burj Qatar of Jean Nouvel, a 45 storey office tower with a textured appearance from a distance that turns into a more delicate traditional Islamic patterning in closer proximity. The third competitor is the mixed use Tornado Tower of Munich based architects SIAT Robinson Pourroy, with spectacular external lighting system created by renowned light artist Thomas Emde. The system is capable of displaying 35,000 different light combinations that foster its presence. Overall, the West Bay scene is becoming an attraction for many international companies.

Scene 5: The Education City

This is unique scene and is believed to be the first precedent worldwide where many international architects are working in the same site and at the same time including Isozaki, Legoretta, and OMA. They are all contributing their own ideas and theories through their practices in creating environments for learning, nurturing, and research. Ricardo Legoretta who continues in his design of the Engineering College of Texas A & M University, at the Education City in Doha, to root his work in the application of regional Mexican architecture to a wider global context. He uses elements of Mexican regional architecture in his work including earth colors, plays of light and shadow, central patios, courtyards and porticos as well as solid volumes. The concept is based on introducing two independent but adjoining masses linked by large atrium; these are named the Academic Quadrangle and the Research Building. The overall expression of the building demonstrates masterful integration of solid geometry and a skillful use of color and tone values, while proposing a dialogue between tradition and modernity. Such a dialogue is also evident in his latest intervention of the Student Center at the Education City that acts as a catalyst for a vibrant environment fostering social and cultural interaction. On the same site, Arata Isozaki designed the Liberal Arts and Sciences building (LAS) which is a focal point for all students in the Education City campus. As a visually striking and architecturally stunning intervention, the building is designed around a theme developed from traditional Arabic mosaics that are evocative of the crystalline structure of sand. This was based on intensive studies to abstract the essential characteristics of the context while introducing new interpretations of geometric patterns derived from widely applied traditional motives.

Scene 6: The Pearl Development

This scene is named the ‘Pearl’ development. Developed by UDC-United Development Company, one of the major real estate developers in the country, this is a man-made island conceived in an exclusive development of four million square meters and 32 Km coastline. Different eclectic and hybrid styles of regional and European architecture are utilized for introducing a distinctive image in the development. Promoting a new lifestyle, the scene includes luxury apartments, town homes, penthouses, and villas, five star hotels, retail, restaurants, entertainment, with an international yachting club that includes three marinas and accommodates over 700 boats. While in the West Bay scene individual buildings compete in shaping the urban image, priority for image making in the Pearl Development is given to the overall urban setting, activities, landscape and water front promenade rather than to buildings individually.

Evolving Questions for a Future Performance in a Future Theater

While the preceding 6 scenes offer glimpses on the nature of the current theater, the performers, and the underlying cultural politics, I should note that emerging scenes are being performed, including KATARA, al-Waab City, and the future city of Qatar, Lusail. While in essence some of these are statements of power that react in a way or another to the drama of cultural politics, they are not only statements of forms and architectural compositions made by name architects for intellectual or enlightened clients, but serious ventures that attempt to speak to the environment, culture, and the postmodern global condition with different degrees of successes. In ending this narrative, I would argue that the performance in the current theater mandates the development of questions for a future performance in a future theater: What are the sustainable qualities (social-environmental-economic) that should be associated with international scenes on entering the hosting culture especially those pertaining to social practices? What are the socio-cultural impacts those scenes have on the locale and how can their negative effects, if exist, be reduced or hopefully eliminated? What is the running cost of those scenes and how they affect the everyday activities of the average citizen? Can there be a position within socio-global aspirations for traditional scenes that are still important for the today’s culture of Qatar? Without a doubt, deserving special attention, it appears that these questions while being integral to the contemporary cultural narrative, they are yet to be matured in future scenes.

Download article as PDF