Selected Topic

Issue 7 - On Canetti – Literature and Architecture: Letters, Words, Buildings (March 2012)

Show articles

Elias Canetti at his working table in London, 1980

Scheuchzerstrasse, Zurich, 1916-1919

Villa Yalta, Zurich, 1919-1921

Elias Canetti during his school time in Zurich

Rämibühl, Zurich, 1919-1921

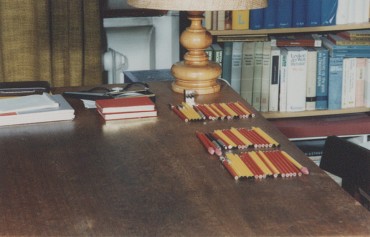

Working Table of Elias Canetti at Klosbachstrasse in Zurich

Tombs of Elias Canetti (left) and James Joyce (right) in the Fluntern Cemetery, Zurich

16.7.2014 – Issue 7 - On Canetti – Sauter Florian, Canetti Elias – Essays

The Shadows

Excerpts from Elias Canetti: The Tongue Set Free - Remembrance of a European Childhood

Zurich – Scheuchzerstrasse, 1916-1919

“I was never told that one does something for practical reasons. Nothing was done that might be “useful.” All the things I wanted to grasp were equally valid. I moved along a hundred roads at once without having to hear that any was more comfortable, more profitable, more productive. It was the things themselves that were important, and not their usefulness. One had to be precise and thorough and know how to advocate an opinion without trickery, but this thoroughness applied to the thing itself and not to some use it might have. There was scarcely any mention of what I might do some day. The thought of a profession receded so far into the background that all professions remained open. Success didn’t mean that one advanced for oneself, success benefited everybody, or it wasn’t true success.”

Villa Yalta, Zurich – Tiefenbrunnen, 1919-1921

“After supper, which we ate together at a long table on the lower floor of the house, I sneaked into the orchard. It lay off to the side, separated by a fence from the actual grounds of the Yalta; we only entered it as a group during the fruit harvest, otherwise it was forgotten. A rise in the ground concealed it from the eyes of the house tenants; no one suspected you were there, you weren’t looked for, even calls from the house sounded so muffled that you could ignore them. As soon as you had slipped unnoticed through the small opening in the fence, you found yourself alone in the evening twilight and you were open to any mute event. It was so since sitting next to the cherry tree on a small rise in the grass. From here, you had a free view of the lake and you could follow the inexorable changes in its color.”

Zurich - Rämibühl, 1919-1921

“The class had been in the square, merloned main building of the Gymnasium, which was thrust, oblique and fairly sober, in to a bend in Rämistrasse, an ascending street. From this building, which dominated the nearby urban landscape, the class was moved in the Schanzenberg (the entrenchment mountain), very close by on its own hill; and, not having been meant as a schoolhouse originally, it had an almost private character. The classroom had a veranda and faced a garden; during lessons, we kept the windows open, and the room was fragrant with trees and flowers; the Latin sentences were accompanied by bird sounds.”

Zurich – Tiefenbrunnen, 1919-1921

“Of the town, I knew the parts facing the lake, as well as the road to school and back. I had been to few public buildings, the music hall, the art house, the theater, and very rarely at the university for lectures. The anthropological lectures took place in one of the guild houses on the Limmat. Otherwise, the old part of town consisted, for me, of bookshops, where I browsed through the “scholarly and scientific” books that were next on the program. Then near the railroad station, there were hotels, where relatives stayed when visiting Zurich. Scheuchzerstrasse in Oberstrass, where we had lived for three years, almost passed into oblivion; it had too little to offer, it was fairly remote from the lake, and if ever I did think of it, it was as if I had lived in some other town. In regard to some districts, I knew no more than the name and gave in, unresistingly, to the prejudices associated with them; I had no idea what people there looked like, how they moved or acted towards each other. Everything that was distant laid claim to me, anything less than half an hour away and in an undesirable direction was like other side of the moon, invisible, nonexistent. You think you’re opening up to the world and you pay for it with blindness towards what’s close by. Incomprehensible is the arrogance with which you decide what concerns you and what doesn’t. All lines of experience are prescribed without your realizing it; anything not to be grasped without letters remains unseen, and the wolfish appetite that styles itself a thirst for knowledge doesn’t notice what escapes him.”

Transl. Joachim Neugroschel

Images (1), (4) and (6) are copyright of Johanna Canetti

Reprinted with the permission of Johanna Canetti

Edited by Florian Sauter

Download article as PDF